How Do Insects Produce Offspring?

How Do Insects Produce Offspring?

When people think of pests, the immediate thought is almost always of the fully-formed critters. Whether they crawl, wriggle, or fly, adult insects are often the worst because they spend their days gathering food and reproducing. But this exact pattern leads us to today’s question: how do insects produce offspring? The elementary answer is “by laying eggs,” but this is actually not the case for every insect species. It is true that cold-blooded creatures generally produce eggs, but every specific animal is different in their process of laying the egg at a certain time and caring for their hatchlings. Let’s explore the primary ways that insects produce eggs and how each one differs in their levels of attachment to their hatchlings.

Oviparous

This is the common egg-laying method that we mentioned earlier. It is popular for good reason, since most insects produce offspring through this practice. Oviparous insects lay eggs that will not hatch immediately upon leaving the mother. The number of eggs completely differs between species, and are either laid one at a time or in batches. The tiny insects will continue to develop inside the egg, nourished by the “yolk” inside rather than by food offered by the mother. Speaking of, most mother insects will either leave their eggs right after laying them or die shortly thereafter. One exception is certain species of earwigs, as they will stay with their eggs until they hatch. As for the majority of insect eggs, they are perfectly fine to be left alone, especially if the mother picked a great hiding spot for them. They have nourishment and a secure shelter within the egg, so oviparous insects have an advantage as soon as they enter the great big world that becomes increasingly more dangerous for insects with each life stage.

Viviparous

Put simply, this is essentially the opposite of oviparous. Viviparous insects give birth to live insects that are past the egg stage. This method is more common with mammals than insects, as humans, dogs, cats, and other warm-blooded beings are viviparous. As for insects, those that are viviparous can sometimes reproduce through parthenogenesis, where they do not need to mate first. The specific appearance and needs of each young insect varies with the species (which we’ll discuss in the subsections), but all of them are no longer trapped inside the egg upon entering the world. The egg develops in the mother before she births the larvae, which can survive alone if necessary. The new insects are fed specific meals by the mother, and will continue to develop from this nourishment until they can confidently survive alone. Aphids are a common example of viviparous insects, as they can birth live females that have their own developing embryos in the summer.

Within viviparity, there are four primary methods that are more specific to the state of the young insect when it is born.

- Ovoviviparous: While less common than being oviparous, ovoviviparous insects are some of the most common pests we see in our yards. The mother insects keep the eggs inside their reproductive tracts until the eggs are set to hatch within the ootheca (or egg case). The eggs have a thinner shell compared to other insect eggs so they can absorb nutrients within the female insect before hatching. Then, the female insect will produce the freshly-hatched offspring, so it’s technically a live birth rather than an egg-laying session. Cockroaches and beetles are the most well-known species to do this, and new ovoviviparous species are being discovered all the time. A study in Zookeys explained how a few female long-horned beetles in the mountains of Borneo were found to have two larvae each inside their bodies. Though they are beetles, long-horned beetles were not previously known to be ovoviviparous. You learn something new every day!

- Pseudoplacental Viviparity: This is a big word for a relatively simple concept, but that is typical of scientific processes. These insects produce embryos that are so underdeveloped that they require specific food in order to survive. The mother insect will also produce a sort of placenta tissue that will be her offspring’s food source for the foreseeable future. This is because the embryos do not have any “yolk” from their eggs to feed upon, so this tissue is the perfect sustenance to give them the nutrients needed to develop into their future life stages. Aphids use this method at various points throughout the year, as well as certain species of earwigs.

- Hemocelous Viviparity: This concept may sound like it’s better suited for a horror movie, but it is completely natural for select insect species. These embryos develop inside the mother as usual, but they have a certain feeding habit that truly sets them apart. They stay in the hemolymph within the mother’s body, which is basically the insect version of blood and vitals. The embryos will then feed from the female’s “blood” until they are more developed and can therefore be birthed. They may even eat other larvae within their mother, which is also a wild diet choice. This whole concept falls under internal parasitism since the embryos are feeding directly from the adult insect on the inside. Gall midges are the popular example of this method, and we are happy to know that this is not the most common reproductive process for pests.

- Adenotrophic Viviparity: Insects that fall under this category hatch very early inside their mother insects. In fact, they hatch so early that the females essentially give birth to fully-grown larvae. Since the embryos can start feeding early on, they grow quickly before being born. The new larvae are often so developed that they pupate immediately after leaving their mothers, such as the case of the tsetse fly. This sub-Saharan fly births one larva at a time and buries it in soil. The larvae eat blood protein while submerged, and then emerge as fattened pupae. The females produce two to four larvae a month, and only have to mate once to do so. Other common insects are bat flies and horse flies.

While each of these methods have their own reasons and statistics, they all fall under the umbrella of viviparous insects. These pests may not have the protective shells that traditional eggs do, but they have the advantage of entering the world as advanced hatchlings that are closer to being independent than eggs are.

Larviparous

Larviparous insects function similarly to adenotrophic viviparous insects, but with a couple key differences. This method is when the mother insects produce full larvae that have spent as much time as possible in the gestation period. The female will not birth the larvae until the offspring are ready to pupate, which they will do soon after being born. The larvae is deposited directly into their food source so they can continue developing while consuming the nutrients they need. Female insects in this category will create hundreds of eggs, but only produce about 25 larvae at a time. Flesh flies are common larviparous insects, and their horrific food source is right in the name. They feed on excrement and decomposing flesh, so the mothers will place the larvae directly into these materials. Forensic scientists actually use flesh flies to determine dates and times relevant to a body, which makes these flies quite the evidence for a case.

Parthenogenesis

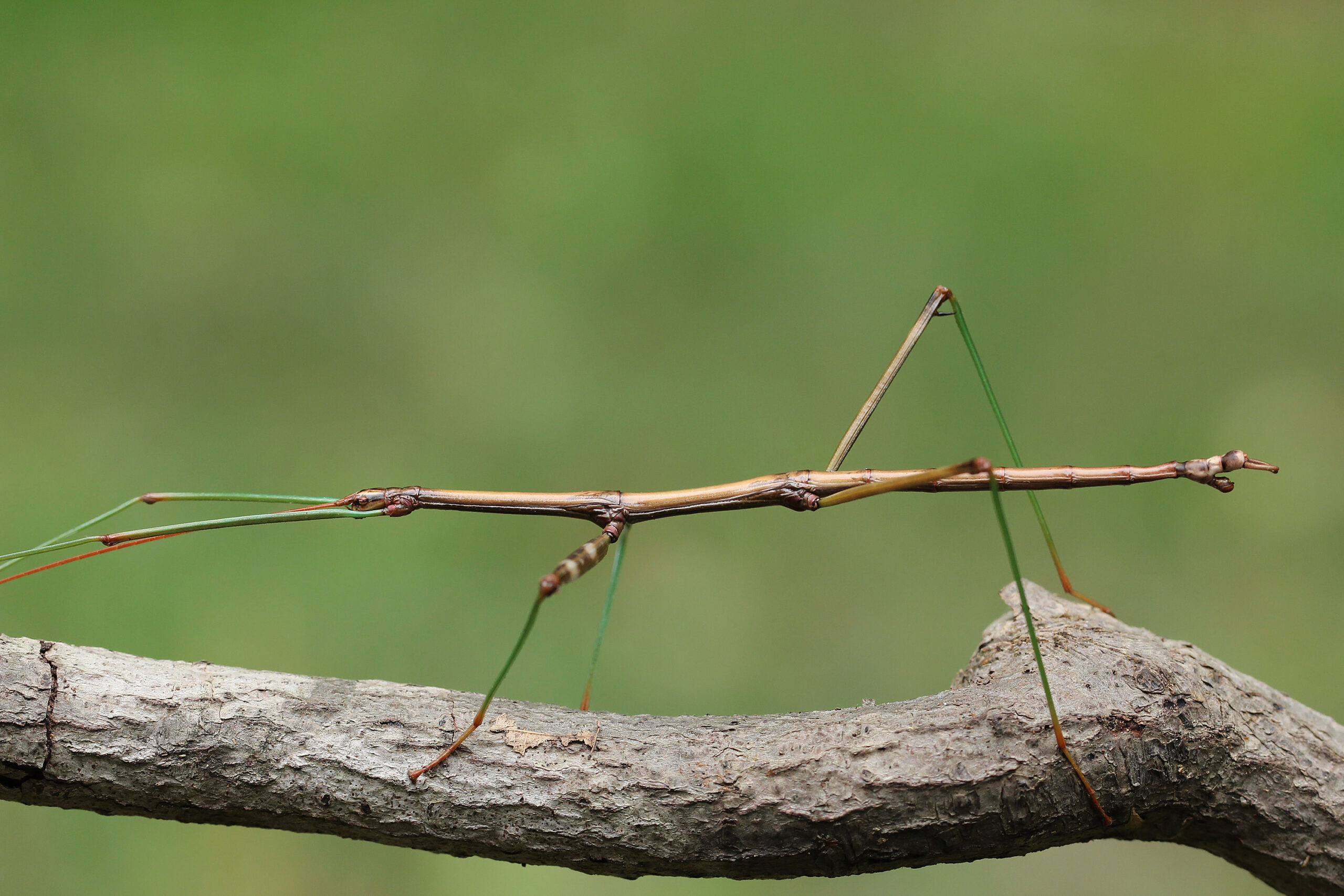

Insects that utilize this process are typically social insects, which explains their prevalence every year. Parthenogenesis is when the insect does not need to mate before producing hundreds of offspring. They may mate once early on, but this is not always necessary. The offspring develop from egg to a fully-formed adult quickly and without relying too much on the mother for food. There is no fertilization involved in this method. This makes it more of a survival strategy than a reproductive method that was naturally formed. It is mainly used in areas with adverse weather patterns and a lack of male insects within that species, so the female insects can continue reproducing regardless of outside circumstances. Some common species that will use this method on occasion are wasps, bees, ants, and stick insects.

Green Provides Solutions for All Pest Life Stages

When pests lay eggs, there often needs to be at least one follow-up treatment after the initial service. This is because insect eggs are so durable that they are almost impossible to penetrate with insecticide, so they will still hatch as normal even when the adults are all eliminated. But one re-treatment a couple weeks later should do the trick in completely solving the problem – that is, if the pest control company is worth their salt. When you receive services from Green Pest Services, you can be sure that your pest problems will be thoroughly addressed every time! Our experienced technicians know the signs to look for when it comes to pest invasions, including the usual egg-laying sites of common pests. Contact us for a free quote on the best pest control services that leaves no pest behind!

Citations

Allen, J. (2016, May 15). Newly discovered beetle gives birth to live young. Biosphere. Available at https://www.biosphereonline.com/2016/05/15/beetle-birth-live-young/ (Accessed on March 22, 2023).

Donovan, P. & Smith, J. (2021, March 3). Insect reproduction. Herpetoculture Network. Available at https://herpetoculturenetwork.com/insect-reproduction/ (Accessed on March 22, 2023).

Flint, M.L. (2013, July). Aphids. UC IPM. Available at (Accessed on March 22, 2023, from https://ipm.ucanr.edu/PMG/PESTNOTES/pn7404.html

Life cycle of flesh flies. (n.d.). Orkin. Retrieved March 22, 2023, from https://www.orkin.com/pests/flies/life-cycle-of-flesh-flies

Oviparity. (n.d.). Amateur Entomologists’ Society. Retrieved March 22, 2023, from https://www.amentsoc.org/insects/glossary/terms/oviparity/

Ovoviviparous. (n.d.). Encyclopedia. Retrieved March 22, 2023, from https://www.encyclopedia.com/science/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/ovoviviparous-0

Vila, I.L. (2017, November 26). The (a)sexual life of insects. All You Need is Biology. Available at https://allyouneedisbiology.wordpress.com/tag/pseudoplacental-viviparity/ (Accessed on March 22, 2023).

Viviparity. (2018, May 29). Encyclopedia. Retrieved March 22, 2023, from https://www.encyclopedia.com/plants-and-animals/zoology-and-veterinary-medicine/zoology-general/viviparity